Please Do Not Tip The Domain Parking Attendants!

Uncle Andrew

Uncle Andrew

We’ve all been there at least once or twice.

You’ve got yourself a hankerin’ to check out the selection and prices, oh, say, Eyebrow Tweezer Warehouse. You figure you can save yourself both a trip in the car and a Google search by simply typing “www.eyebrowtweezerwarehouse.com” into your Web browser’s address bar.

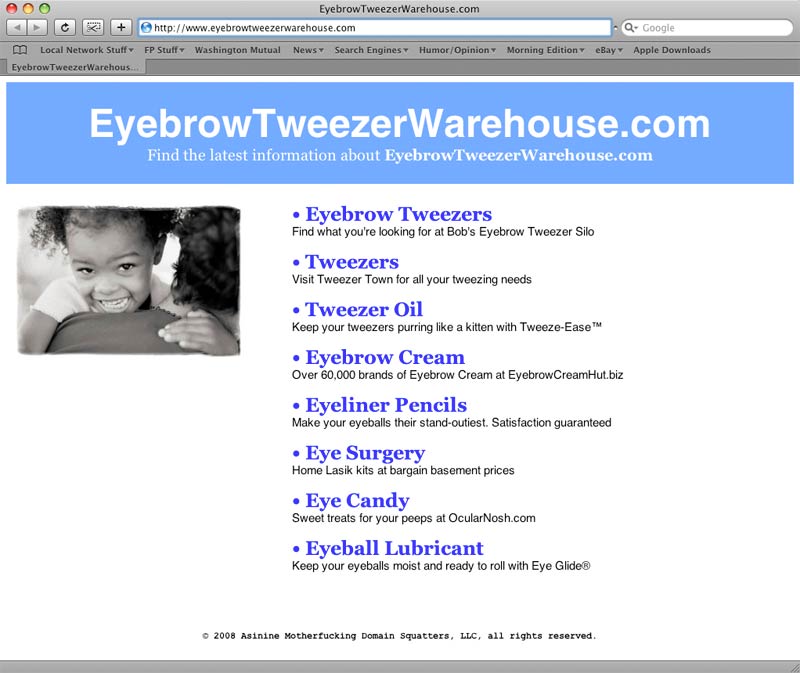

Only instead of the Web site for Eyebrow Tweezer Warehouse, you get something that looks like this:

Not the site you were looking for, but a page of links to sites whose names or content seem peripherally related to your intended destination. Heck, the real Web page for Eyebrow Tweezer Warehouse might be listed among the links, along with the sites of half a dozen of their closest competitors.

For God’s sake, don’t click on any of the links. Close the window, open a new one, and start over, this time from your favorite search engine.

The page you have reached is an example of what is called “domain parking”, one of a group of related practices of varying helpfulness and legitimate function on the Web.

At its core, domain parking simply means setting up a basic, placeholder Web site at a given domain name. Many individuals and organizations park a domain to stake out a Web presence for future development. For instance: although I already have a lovely little piece of virtual real estate picked out for my blog, I might also choose to reserve the domain name andrewlenzer.com—I haven’t, but I could—and instead of going to the trouble of building another Web site or pointing andrewlenzer.com at my blog, I might just put up a single, rudimentary Web page to indicate that the domain is active and that it belongs to me. Lots of Internet Service Providers and domain hosting companies automatically put up domain-parking pages for their clients who do not wish to build a full Web site, at least for the moment.

The basic and largely innocuous practice of domain parking long ago spawned a number of varied, often less savory business endeavors, as soon as some enterprising souls figured out that they could make a farthing or two off of them. The primordial form of this new parasite of the information economy was cybersquatting, the act of reserving a domain name for the purpose of misrepresenting one’s relationship to the perceived person or organization represented. (The classic peta.org versus peta.com tussle is a prominent example of this sort of thing, though there are many who argue that, in that particular case, the squatter—an organization calling itself People Eating Tasty Animals—was doing so as a form of parody of the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and should therefore have not been forced to relinquish the domain name.)

Many early cybersquatters attempted to use their parked domains as a tool of ransom or blackmail against the “proper” holder of a trademark or other distinctive word or phrase. Federal legislation regulating this sort of behavior has since discouraged the bulk of these attempts. Other forms of largely commercial domain parking include typosquatting (parking a domain with a common misspelling of a prominent domain name, such as oficemax.com instead of officemax.com). There’s even an amazing form of typosquatting that revolves solely around the accidental omission of the “o” from “.com”. A Canadian physician-turned-Net-mogul named Kevin Ham struck a deal with the country of Cameroon (legitimate holder of the “.cm” TLD, or top-level domain) to take control of it, and now owns a .cm equivalent to just about any prominent .com domain you can think of.

The most lucrative expression of cybersquatting is without a doubt the practice of using parked domains to capture “type-in traffic“—Web surfers entering domains blindly into their browser’s address bar. The owners then use the parked domain(s) to host Web pages stuffed with hyperlinks to other sites—as per my example above—and reap pay-per-click fees for every visitor who clicks on any of the links.

All of this is, by all accounts, extremely profitable. Kevin Ham’s interests alone are said to net about $70 million per year in ad revenue, though he doesn’t release those numbers to the public. Solid numbers are hard to pin down, but with even rinky-dink civilian domain parkers earning thousands of dollars click-through fees per year, the total worldwide yield from this sort of advertising has to be in the billions.

All for a totally unnecessary “service” that exists solely to save the average surfer from having to type additional characters in the address bar.

I am absolutely stymied by the behavior exhibited by a plurality of my fellow Netizens when presented with such a scenario. There’s a strange sort of credulity that seems to afflict many consumers of Internet culture when coming across stuff online, from emailed Net rumors to Web pages (Bonsai Kitten, anyone?), that they would never display out in the meat world. I’ve waxed pedantic about this before.

Imagine if you will walking into, say, your local Best Buy, only to discover once inside that the store you had entered was actually called “Bist Buy”. Their store facade is identical to a Best Buy’s, the interior layout is quite similar to a Best Buy, and the employees all wear similar blue-polo-shirt-and-tan-pants uniforms as the employees at a Best Buy. But it’s clearly not the store it had initially—and intentionally—misrepresented itself as.

At this point, would you say to yourself, “I know this store isn’t what it purports to be, and I’ve never heard of this outfit in my life. But heck, as long as I’m here I might as well look around, check out the merchandise, sign up for their monthly newsletter, maybe even plonk down a big ol’ wad of cash for a plasma TV”? Or would you instead backpedal out of that store as fast as your highly alarmed little legs would carry you?

Even if the prospect of bankrolling these spurious middlemen doesn’t bother you, the potential threat to your privacy ought to. Clicking on a link in one of these sites will usually place any number of tracking cookies on your computer, so that they can follow your movement through the infosphere and sell that data to marketers. Even worse, many parked sites are created and run by what amounts to criminal organizations, existing solely to disseminate trojans, adware and other poison to unsuspecting, unprotected computer users.

So if you happen to mistakenly blunder across one of these handy-dandy billboards whilst jaunting on the Infobahn, please do not tarry, and for the love of Deus ex Machina do not stop to sample their humble wares. These sites are erected by people who are at best avaricious and opportunistic, and at worst Information Superhighwaymen.

Instead, tip your hat, bid them good day, and hightail it out of there as if all the keystroke loggers in hell were after you.